Savage Beginnings

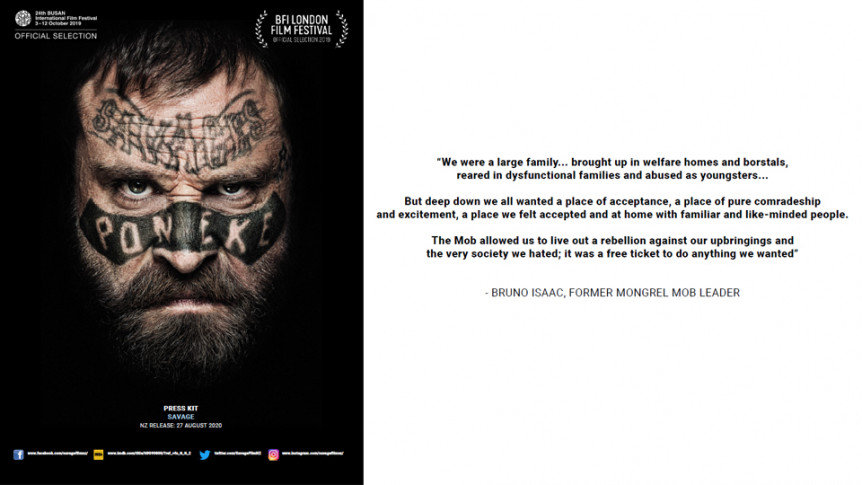

The newly released New Zealand movie Savage directed by Sam Kelly, is inspired by stories from the nation’s boys homes from 1950 to 1999 and the early history of gangs. Savage follows Danny, a fictional character, across three decades of his life, taking a deeper look at a boy who grows into the brutal enforcer of a gang and to understand how he got there. Officially premiered at Auckland’s Sylvia Park in September, the film is part of the initiatives associated with the Royal Commission of Enquiry into Abuse in Care.

Inspired by stories from New Zealand’s boys homes and the early history of our gangs, Savage follows Danny across three different ages at important junctures that push and pull him towards and away from gang life.

Each chapter of Danny’s life is a complete short story set in a defining time for New Zealand gangs; from the abusive state-run homes of the 1960s to the emerging urban gang scene in the 70s where disenfranchised teenagers created their own families on the streets; to the 80s when gangs became more structured, criminal and violent.

The three chapters combine to create a deeper look at a boy who grows up to become the brutal enforcer of a gang and to understand how he got there.

Savage is about Danny’s search for belonging and connection and explores the notion of family. He is torn between his real family and his gang family and must choose where he belongs.

Q&A WITH WRITER / DIRECTOR SAM KELLY

Where did Savage come from?

“Despite this story being set in the foreign (to me) world of gangs, it felt like the most personal script I’ve ever written. It’s about a character who feels lost, isolated from the world around him and yearning for something more. The script was the expression of a masculine primal scream, of wanting to find belonging, but struggling to do so,” he says.

“I struggle to connect with people. My instinct is to curate a persona that will be tolerated. It comes from the idea that there’s something about me that’s shameful, loathsome, and if people saw who I truly was, they would reject me.

“When Danny is a child and a teenager, he must harden to survive in the world, to put on a mask. Then, as an adult, this hardened mask isn’t serving him, it prevents real intimacy, real connections. To re-connect with his family, he must embrace vulnerability… to take off his mask,” he adds.

“To add to the struggle, Danny exists in an intensely masculine, violent world where he can’t openly express these emotions because it would be viewed as a weakness to be exploited.”

WHY THE GANG WORLD?

“I come from Porirua, a place where gang members are a part of the fabric of the community. And I have friends who were directly impacted by gang violence, which initiated a deeper look into a community I’ve been researching and connected to ever since,” says Sam.

“I’ve wrestled with the question of why young people are drawn into gangs and what they find there. I also spent a lot of time with kids and leaders involved in at-risk youth programmes.

“Making my short film, Lambs about at-risk youth, draw me closer to the gang world. While researching Lambs, I spent time with a Porirua youth gang and the met several former and current Mongrel Mob and Black Power members. Some gang chapters have a rule of not taking to outsiders, but I was able to gain their confidence and listen to them talk at length about their closed world and life experiences,” he adds.

“They told me about their values, structure, criminality, stories of extreme violence and internal conflicts … but it was the stories of their childhood journeys towards becoming gang members that I found the most affecting,” he recalls.

“Many came from abusive homes, were removed and placed in state care where they suffered horrific abuse and, afterwards, looked to join other outcasts in a new family unit – a gang.

“The New Zealand state failed these guys, particularly the abuse they suffered in state care. And when they reported the abuse to those in authority positions, they were shut down and ridiculed. New Zealand society went on while the experience of these kids was swept under the covers.

“More than anything, these guys want to be heard ... like ‘This happened to me’!”

WHAT WILL VIEWERS TAKE FROM THE FILM?

“Society often depicts gang members as morally bankrupt people who have made terrible choices in their lives and are fully responsible for their own situation,” says Sam.

“My philosophy in life, however, is to seek to understand, and to see individuals as products of their environment and personality traits, which I believe are a product of luck.”

From the director’s meetings, interviews and research of gang members and at-risk youth, there were common environmental factors. Many were raised in homes with abuse and neglect as their parents struggled to deal with urbanisation, alcohol and poverty, among other factors. The state removed many children from their homes in the 1960s and 70s. Some were for minor offences, which saw them put in state-run institutions where domineering untrained staff had scant regard for the welfare of children. Emotional, physical, and sexual abuse by staff was rampant and the children’s attempts to report the abuse was usually met with incredulity and dismissiveness, as ‘children should be seen and not heard’. As a result, these children developed hostile relationships to authority figures and many ran away.

Pasefika Proud Pathways for Change 2019-2023 Pacific families and communities are safe, resilient and enjoy wellbeing.

Pasefika Proud is a social change movement – ‘by Pacific for Pacific’ – to boost wellbeing for Pacific families and transform attitudes, behaviours and norms that enable violence. Our name and strapline embody our strengths-based, community-led approach:

Pasefika Proud: Our Families, Our People, Our Responsibility